Imagine stepping into your backyard orchard each season, harvesting baskets of sun-ripened fruit straight from the tree — juicy, flavorful peaches in midsummer or crisp, aromatic apples in fall. For many home gardeners and tree enthusiasts, this dream starts with one crucial decision: choosing between stone fruits and pome fruits. Understanding the differences between these two groups isn’t just botanical trivia; it directly impacts your success in planting, pruning, pest management, and overall tree health. Whether you’re a beginner planning your first fruit trees or an experienced grower optimizing your space, knowing these distinctions helps you select the right varieties for your climate, avoid common pitfalls like poor drainage issues or pollination failures, and enjoy abundant, high-quality harvests year after year. 🌳

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore the core botanical differences, practical growing needs, tailored care techniques, and real-world decision-making tools. By the end, you’ll have the expert-level knowledge to grow thriving fruit trees that suit your garden perfectly.

What Are Stone Fruits and Pome Fruits? A Botanical Breakdown

Both stone fruits and pome fruits belong to the Rosaceae family (the rose family), sharing traits like beautiful spring blossoms and similar pest vulnerabilities. However, their fruit structures and subfamily classifications set them apart dramatically.

Defining Stone Fruits (Drupes) 🍑

Stone fruits, also known as drupes, feature a classic three-layer structure:

- Exocarp: The thin outer skin (e.g., the fuzzy peach peel or smooth plum skin).

- Mesocarp: The juicy, edible flesh we love to bite into.

- Endocarp: The hard, woody “stone” or pit that encases a single seed.

This pit protects the seed and gives the group its name. Stone fruits typically produce fruit on one-year-old wood, leading to vigorous, short-lived growth spurts.

Common examples include:

- Peaches and nectarines

- Plums

- Apricots

- Cherries (sweet and sour varieties)

- Almonds (technically a stone fruit, though grown for the seed)

These fruits often burst with summer sweetness and are prized for fresh eating, preserves, and baking.

Defining Pome Fruits 🍎

Pome fruits are accessory fruits — the edible fleshy part develops from the floral tube (hypanthium) surrounding the ovary, not just the ovary wall itself. The “true” fruit is the papery core containing multiple small seeds (usually 5–10), enclosed in a leathery membrane.

The term “pome” derives from the Latin pomum, meaning apple — fitting, since apples are the classic example.

Common examples include:

- Apples

- Pears (European and Asian varieties)

- Quince

- Less common: Medlar, loquat (sometimes classified separately but botanically similar)

Pome fruits tend to store longer and develop fruit on older wood, including spurs that produce reliably for years.

Quick Comparison Table: Stone vs. Pome at a Glance

| Aspect | Stone Fruits (Drupes) | Pome Fruits |

|---|---|---|

| Fruit Anatomy | Single hard pit with one seed | Central core with multiple small seeds |

| Edible Parts | Skin + juicy flesh around pit | Fleshy accessory tissue + core (seeds usually discarded) |

| Botanical Subfamily | Prunoideae (Prunus genus dominant) | Maloideae (Malus, Pyrus) |

| Typical Lifespan | 15–25 years (peaches shorter-lived) | 30–50+ years (longer-lived) |

| Fruiting Wood | Mostly 1-year-old shoots | Spurs on older wood |

This structural divide influences everything from pruning style to disease susceptibility.

Key Botanical and Structural Differences 🔍

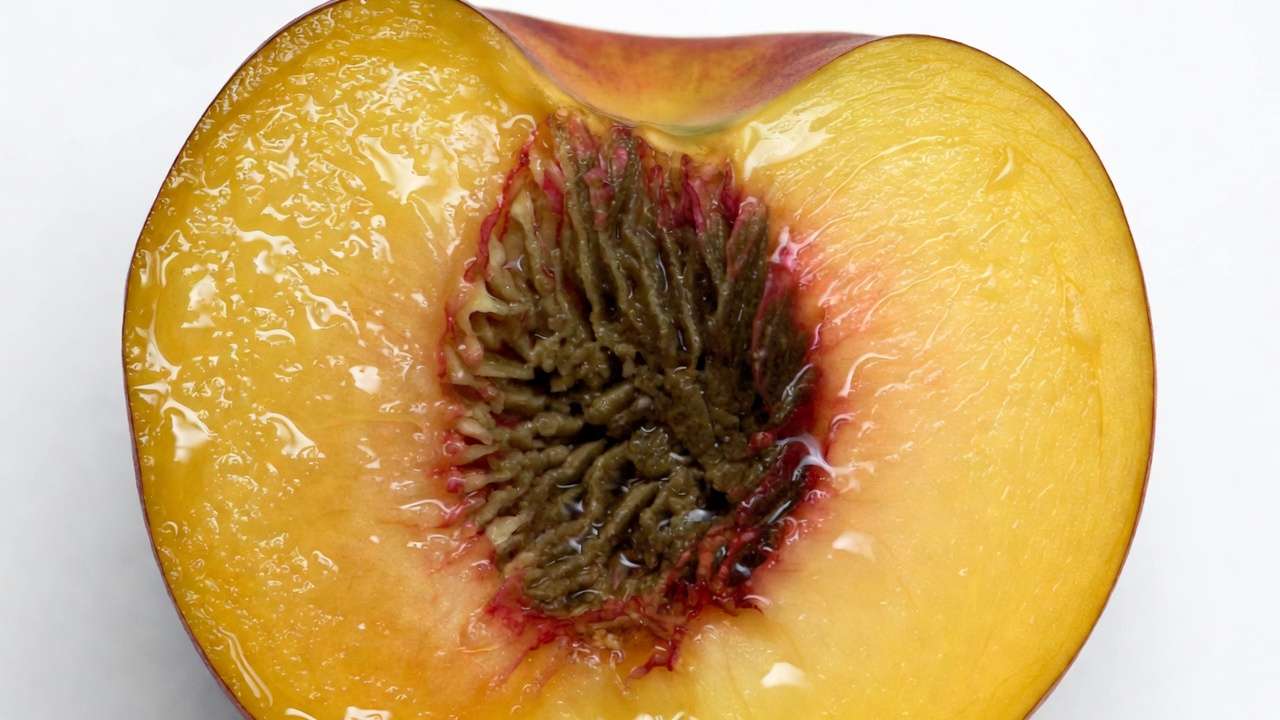

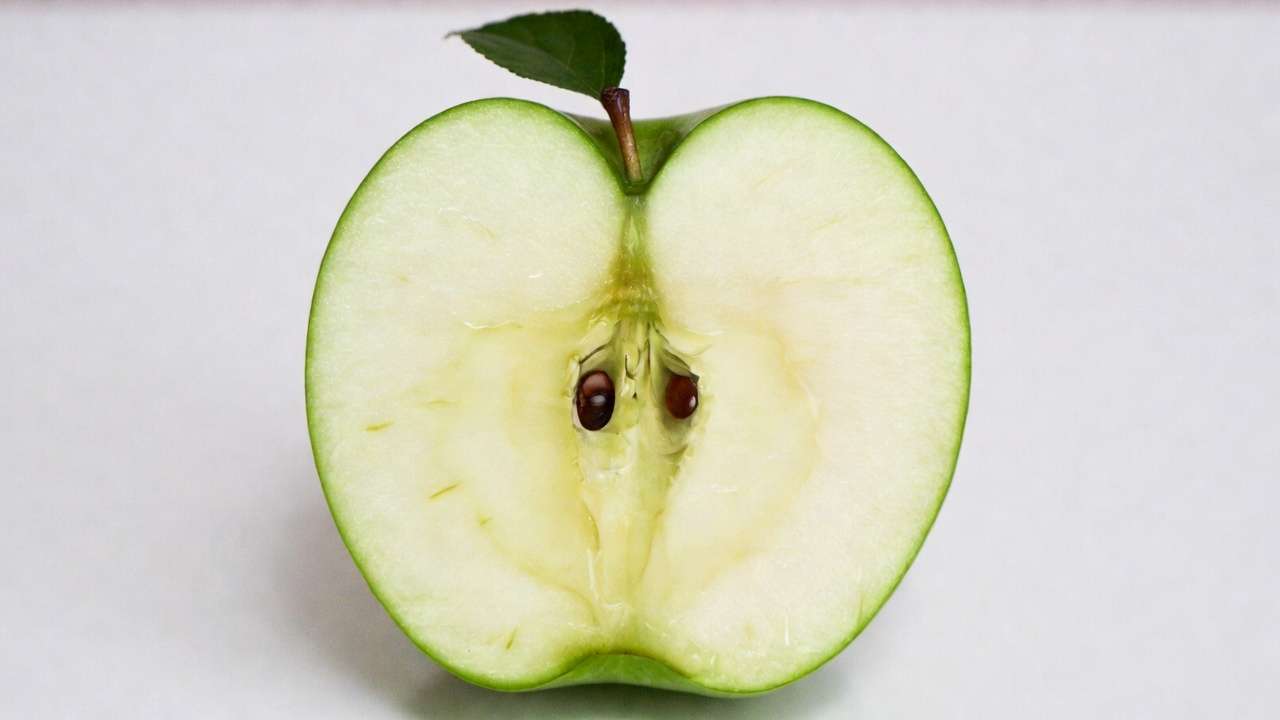

The most obvious difference appears when you slice the fruit open.

Fruit Anatomy Side-by-Side

Cut a peach in half: You’ll see one large, hard pit in the center — that’s the endocarp protecting the seed. The flesh melts away easily from the stone in freestone varieties or clings stubbornly in clingstone types.

Slice an apple: The core is a tough, star-shaped chamber holding several seeds, surrounded by crisp flesh that extends from the floral receptacle. No single “stone” here — the seeds are embedded but accessible.

These differences affect seed dispersal in nature (animals eat the flesh and discard the pit vs. core) and how we process them (pitting stone fruits vs. coring pomes).

Plant Family and Growth Habits

Both groups thrive in temperate climates, but stone fruits (Prunus spp.) often grow more vigorously early on, with shorter tree lifespans and higher sensitivity to wet soils. Pome fruits (Malus, Pyrus) develop stronger, more permanent structures with spur systems that bear fruit for decades.

Stone trees tend to be more compact when young but require aggressive renewal pruning to maintain productivity.

Growing Needs and Climate Suitability 🌤️

Climate match is perhaps the biggest make-or-break factor for fruit tree success.

Chill Hours and Hardiness

Chill hours (accumulated time between 32–45°F / 0–7°C during dormancy) trigger uniform blooming and fruit set. Insufficient chill leads to erratic blooming and poor crops.

- Pome fruits: Higher requirements — apples often 500–1,000+ hours; pears 600–800. They bloom later, reducing frost risk in marginal areas.

- Stone fruits: Vary widely — peaches 200–1,000 (low-chill varieties for warmer zones); cherries 500–1,200; plums/apricots 400–900.

In cooler regions, pome fruits excel reliably. In warmer subtropical areas, low-chill stone fruits (e.g., Florida-specific peaches) perform better. Always check your local chill hour average before planting.

Soil, Sun, and Water Requirements

Both demand full sun (6–8+ hours) and well-drained soil to prevent root issues.

- Stone fruits: Extremely intolerant of poor drainage (“wet feet” cause root rot, especially in peaches). Prefer sandy loam; raise beds if needed.

- Pome fruits: More forgiving of clay soils but benefit from organic matter and consistent moisture.

pH 6.0–7.0 works for both. Mulch heavily to retain moisture and suppress weeds.

Pollination and Planting Essentials 🐝

One of the most frequent frustrations for new fruit tree growers is poor or no fruit set — often due to overlooked pollination needs. This is where stone and pome fruits diverge significantly.

Self-Fertile vs. Cross-Pollination Needs

- Stone fruits: Many are self-fertile (self-pollinating), meaning a single tree can produce fruit without a partner nearby. Peaches, nectarines, most apricots, and some plums (e.g., European types like Italian Prune) fall into this category. Sweet cherries often require cross-pollination, while tart cherries are usually self-fertile. This makes stone fruits more beginner-friendly for small yards.

- Pome fruits: Most apples and many pears require cross-pollination from a compatible variety blooming at the same time. A lone apple tree might flower beautifully but yield little fruit. Exceptions exist (e.g., some self-fertile apples like Golden Delicious can set partial crops alone, but yields improve with a partner). European pears often need cross-pollination, while Asian pears are more self-fertile.

Expert tip: Always check bloom overlap charts from university extensions (e.g., apples in bloom group 3 pair well with group 2–4). Plant pollinators within 50–100 feet for best bee transfer.

Spacing, Rootstocks, and Dwarf Varieties for Home Gardens

Home gardeners often have limited space, so choosing the right rootstock is key to controlling tree size without sacrificing fruit quality.

- Stone fruits: Semi-dwarf (e.g., on Citation or Krymsk rootstocks) reach 12–18 feet; true dwarfs are less common and sometimes less vigorous. Space standard trees 15–20 feet apart, semi-dwarfs 10–15 feet.

- Pome fruits: Excellent dwarfing rootstocks available — apples on M9 or M27 (8–12 feet tall), pears on OHxF series. These allow planting in small yards or even large containers. Space dwarfs 8–12 feet apart.

Plant in early spring (or fall in mild climates). Dig holes twice as wide as the root ball but no deeper; avoid burying the graft union. Water deeply after planting and stake young trees against wind.

Pruning and Training: Why Techniques Differ ✂️

Pruning isn’t just about shaping — it’s essential for light penetration, air circulation, disease prevention, and directing energy to fruit production. The two groups demand different approaches because of where they bear fruit.

Pruning Stone Fruits — Open Vase Method

Stone fruits fruit primarily on one-year-old wood (last season’s growth), so the goal is an open-center “vase” shape with 3–4 main scaffold branches.

- Timing: Late winter to very early spring (before buds swell but after major freezes risk passes) — crucial to avoid bacterial canker spread in wet conditions.

- Steps:

- Remove any dead, damaged, or crossing branches.

- Select 3–4 strong outward-facing branches at wide angles (45–60°).

- Cut back to outward buds; head shoots to encourage branching.

- Thin vigorous watersprouts in summer.

- Common mistake: Over-pruning young trees — they need structure first!

This open shape maximizes sunlight to developing fruit and reduces brown rot risk.

Pruning Pome Fruits — Central Leader or Modified Leader

Pome fruits bear on spurs (short, stubby branches) that live for years on older wood, so maintain a central trunk with well-spaced laterals.

- Timing: Dormant season (winter).

- Steps:

- For central leader: Keep one dominant upright trunk; remove competing leaders.

- Modified leader: Allow 2–3 main scaffolds after 3–4 years.

- Thin out crowded spurs every few years; renew by cutting back old fruiting wood.

- Summer pinching controls vigor.

- Goal: Balanced pyramid shape for light and strength.

Thinning Fruit for Better Quality

Overcrowded fruit leads to small, diseased crops — thin aggressively!

- Stone fruits: Thin to 4–6 inches apart on shoots (peaches especially need heavy thinning for large fruit).

- Pome fruits: Thin clusters to 1–2 fruits, spaced 6–8 inches apart (hand-thin apples/ pears in early summer).

Thinning improves size, flavor, and reduces branch breakage.

Pest and Disease Management — Group Similarities and Differences 🛡️

Both groups face Rosaceae-family pests, but prevention strategies vary.

Common Issues for Both Groups

- Aphids, scale, codling moth (worse on pome), spider mites.

- Fungal diseases thrive in humid conditions — improve airflow with proper pruning.

Stone Fruit-Specific Challenges

- Peach leaf curl: Red, puckered leaves in spring — treat with copper fungicide in dormancy.

- Brown rot: Devastating on ripening fruit — remove mummies, thin fruit, apply fungicides pre-bloom.

- Bacterial canker: Gummy lesions — prune in dry weather, avoid wounds.

- Plum curculio: Small weevils scar fruit — use traps and sanitation.

Pome Fruit-Specific Challenges

- Apple scab: Black spots on leaves/fruit — plant resistant varieties (e.g., Liberty), fungicide sprays.

- Fire blight: Bacterial wilt (shepherd’s crook shoots) — prune 12 inches below infection, use resistant cultivars.

- Cedar-apple rust: Orange galls — avoid nearby junipers or use resistant apples.

- Powdery mildew: White coating — improve air flow, sulfur sprays.

Integrated Pest Management Tips for Home Growers

- Choose resistant varieties (e.g., disease-resistant apples like Enterprise, Liberty).

- Monitor weekly with traps and visual checks.

- Use organic options: Neem oil, insecticidal soap, beneficial insects.

- Cultural controls first: Sanitation (remove fallen fruit/leaves), proper spacing/pruning.

- Spray only when needed — follow extension calendars for timing.

Many home growers achieve good results with minimal sprays by focusing on prevention.

Best Varieties for Home Gardeners 🌟

Selecting proven performers reduces headaches and boosts success.

Top Stone Fruit Picks 🍒

- Peaches: Reliance (cold-hardy, disease-tolerant, 800–1,000 chill hours), Contender or Redhaven (reliable flavor).

- Plums: Santa Rosa (self-fertile, juicy), Italian Prune (great for drying).

- Cherries: Stella (self-fertile sweet), Montmorency (tart, self-fertile).

- Apricots: Moorpark or Goldcot (reliable in suitable climates).

Look for low-chill options (e.g., Florida Prince peach) if in warmer zones.

Top Pome Fruit Picks 🍏

- Apples: Liberty or Enterprise (scab/fire blight resistant), Honeycrisp (popular flavor), Golden Delicious (good pollinizer).

- Pears: Bartlett (classic), Moonglow (fire blight resistant), Asian pears like Shinseiki (self-fertile, crisp).

Prioritize disease-resistant cultivars for low-maintenance success.

Which Should You Grow? Decision Guide

Choosing between stone fruits and pome fruits ultimately comes down to your personal goals, garden conditions, and willingness to invest time in maintenance. Here’s a clear, side-by-side decision framework to help you decide.

Quick Pros & Cons Checklist

| Factor | Stone Fruits (Peaches, Plums, Cherries, etc.) | Pome Fruits (Apples, Pears, Quince) |

|---|---|---|

| Ease for Beginners | Easier (many self-fertile, quicker to fruit) | Moderate (most need cross-pollination partners) |

| Time to First Harvest | 2–4 years | 3–6 years |

| Annual Maintenance | Higher (aggressive annual pruning, heavy thinning, disease vigilance) | Moderate (spur-based pruning, less frequent heavy thinning) |

| Tree Lifespan | Shorter (15–25 years typical) | Longer (30–50+ years possible) |

| Space Requirement | Moderate (semi-dwarf common) | Flexible (excellent dwarf options for small yards/containers) |

| Climate Flexibility | Better in warmer, lower-chill areas | Better in cooler, higher-chill regions |

| Yield Consistency | Can be boom-or-bust (frost, disease, alternate bearing) | Generally steadier with good pollination |

| Fruit Storage | Short shelf life (eat fresh or preserve quickly) | Excellent storage (months in cool conditions) |

| Flavor & Versatility | Intense summer sweetness; great for fresh eating & canning | Crisp texture, wide range of flavors; superb for eating, baking, cider |

Real-Life Scenarios – Which Group Fits Best?

- Small urban or suburban yard (limited space) → Go with pome fruits on dwarf rootstocks. You can plant 2–3 compatible apple or pear varieties and still have room for other plants. 🍏

- Warm climate with mild winters (low chill hours) → Choose stone fruits — select low-chill peaches, plums, or apricots bred for southern regions. 🍑

- Cold climate with long winters → Pome fruits shine here — apples and pears handle deep freezes better and have higher chill requirements naturally met. ❄️🍐

- Beginner with only one or two trees → Start with self-fertile stone fruits (e.g., a Reliance peach or Stella cherry) for quicker rewards and simpler pollination. 🌸

- Long-term investment & low-intervention garden → Plant pome fruits with disease-resistant varieties — they reward patience with decades of production. 🌳

- Love fresh summer fruit & preserves → Prioritize stone fruits for that classic juicy experience. 🍒

- Want fruit you can store through winter → Pome fruits win hands-down — apples and pears keep for months. 🥭

Many gardeners successfully grow both groups in the same yard — just group them by similar needs (e.g., separate irrigation zones if drainage varies) and stagger bloom times to support pollinators year-round.

Conclusion

The divide between stone fruits and pome fruits is far more than a botanical curiosity — it’s the foundation for making smart, site-specific choices that lead to healthy trees and delicious harvests. Stone fruits reward you with explosive summer flavor and relatively quick returns, while pome fruits offer longevity, storage potential, and graceful structure over many years.

Whichever path you choose, success starts with three fundamentals: matching the right varieties to your local chill hours and soil conditions, committing to proper pruning and thinning, and staying proactive with integrated pest management. Start small, observe how your trees respond to your microclimate, and don’t be afraid to experiment — every seasoned fruit grower began with their first hopeful planting.

Ready to bring home some new trees? Whether you plant a juicy peach that drips sweetness in July or a crisp apple that stores through winter, the joy of picking fruit you grew yourself is unmatched. 🍑🍎

Which will you try first — stone or pome? Drop a comment below and share your garden plans — I’d love to hear what you’re growing!

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the main difference between stone fruits and pome fruits? The core difference is fruit anatomy: stone fruits (drupes) have a single hard pit enclosing one seed, while pome fruits have a central core with multiple small seeds surrounded by accessory flesh from the floral tube.

Are cherries stone fruits or pome fruits? Cherries are stone fruits (drupes), just like peaches, plums, and apricots. They have a single hard pit.

Do stone fruits need cross-pollination? Many do not — most peaches, nectarines, apricots, and European plums are self-fertile. Sweet cherries usually require a compatible pollinator, while tart cherries are often self-fertile.

How often should I prune my apple tree vs. peach tree? Prune both annually during dormancy. Peaches need aggressive open-vase pruning every year to renew one-year-old fruiting wood. Apples require lighter maintenance pruning to preserve spurs and maintain shape — renewal pruning every few years.

Can I grow both stone fruits and pome fruits in the same garden? Yes! Many home orchards do. Just ensure good spacing, similar sun/soil needs, and consider grouping by water/drainage preferences (stone fruits are pickier about drainage). They can even support each other by extending the pollinator season.

Thank you for reading this in-depth guide — happy planting and enjoy every bite from your trees! 🌱🍒